David Chan asked A.A. Murakami (Alexander Groves and Azusa Murakami) 11 questions about their creative process. Here is what they had to say:

David Chan (DC) is a Hong Kong and Shanghai-based curator who works with Pearl Lam Galleries and is the previous director of Osage Gallery and the Shanghai Gallery of Art at Three on the Bund.

A.A. Murakami (AAM) are the artists behind Studio Swine (Super Wide Interdisciplinary New Explorers). Working across the media of sculpture, film, and immersive installations, their work explores themes of regional identity and the future of resources in the age of globalization

1.DC: How would you define your art practice or explorations?

AAM: We would say the driving force behind our practice is an interest in materials, both as a way to explore the world and how humans can coexist with the natural less destructively. We have a fascination with the way materials shape us, our cities and culture, our value systems, etc.We want to work on the edge of what is possible, that blurred line between a dream and reality. It’s a line that is always shifting and we seek to occupy by combining material research with new technology and combining our different backgrounds in art and architecture.

2. DC: What are the shifts between the edges of dream and reality?

AAM: As Arthur C. Clark said, “The only way of discovering the limits of the possible is to venture a little way past them into the impossible.” For us, this means doing projects that can be speculative and visualizing something not yet possible to make part of it real. So, we might design a system for collecting plastic at sea to make mobile factories onboard boats, and we actually go to sea and manifest part of this idea for real.

We are interested in the art in science and the science in art and how we can combine the two to bring into the world new experiences and new art forms. Most tech art relies on quite familiar forms of interfaces, projections, LED interfaces, and VR, basically different forms of digital screens; however, we spend more and more of our lives looking at screens, so we don’t want to make art that relies on the same familiar interfaces with technology, which in our view doesn’t make our lives better or our experience of the world richer.

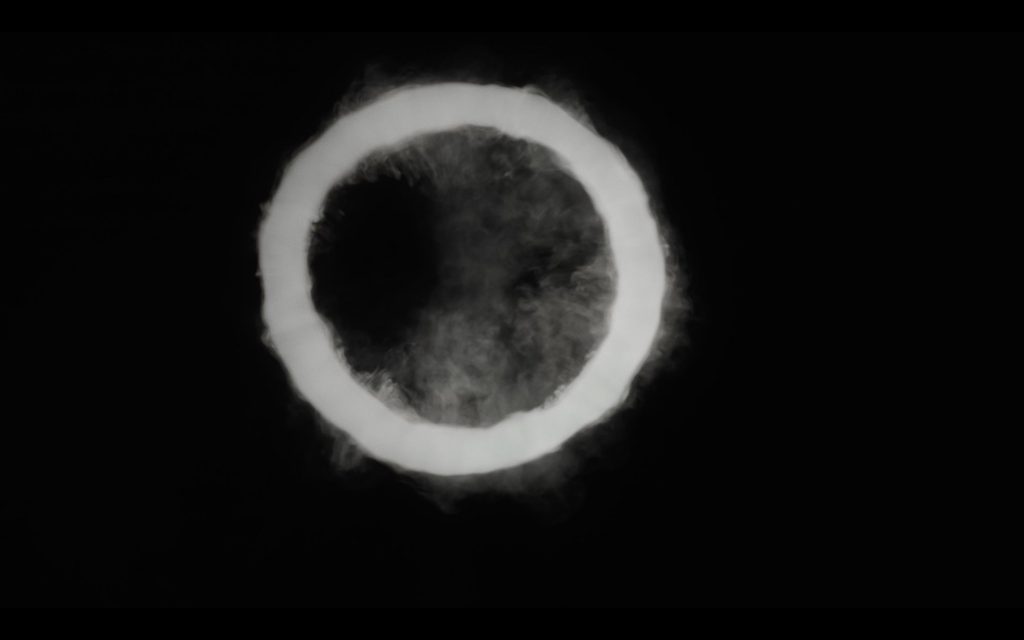

We believe the future is integrating technology into our lives in invisible ways, indistinguishable from natural phenomena like rain, in installations or works we call ‘unnatural phenomena’.

We are interested in the ephemeral and the material qualities of real substances that can have a physiological effect on the viewer by not just engaging through sight or sound but also scent and touch, which bypass the language part of the brain and shortcut to some feeling or memory.

3. DC: According to your statement, your practice intends to combine rich and emotional narratives with rigorous spatial awareness. Would you mind elaborating on this point?

AAM: Azusa studied architecture, and I studied art, then we both took a product design post-graduate course, which is where we met. So, I think we have this desire to fuse what can represent the essence of these disciplines: to make one feel and to organize space.

When we started in design, we saw the functional side of design as frivolous, often pointless. For example, the most common archetype of design is a chair, whose function is to sit on. Over the last 150 years, mass production has solved this problem; there are probably enough chairs to seat the population of the world. But the chair is also a vehicle for ideas. One of the vital roles of design is to express the times in which we live and where we want to go as a civilization. Design and art can create a space, telling stories and evoking a feeling is the focus of our practice.

4. DC: Can you tell us about the impetus and concept behind your first collaborative project, the Sea Chair?

AAM: We were listening to BBC Radio 4 one night, and there was a science documentary about sea plastic. It was 11 years ago, and the first time we heard about the problem. They were recording from a sailing heading across the Atlantic with marine biologists sampling the water for plastic. It wasn’t at the time widely known, and the concept of being able to fish up this human-made material in the middle of the ocean fascinated us.

We had the task of making a chair and had struggled to justify creating another chair in a world full of chairs. We had the idea of making a plastic chair that wasn’t from a factory to be shipped globally but was made on a boat with plastic waste fished out of the sea with a geographical location.

5. DC: A.A. Murakami (Studio Swine) “saw creating as really something problematic in that it usually relied on making more stuff in a world already full of things, fueling endless overconsumption and being a drain on the planet’s finite resources.” What are the possible solutions for this dilemma in the field of art and design?

AAM: While art represents a tiny amount of stuff compared to industrial mass production, its influence on culture is immeasurably vast. So, I think there is a responsibility to consider the environmental footprint of art, as it is linked so strongly to aspiration and the culture of consumption.

We have approached the problem by looking at the materials we use and the lifespan of the work. Sustainability used to be seen as this undesirable frumpy thing that resulted in work that looked like Weetabix. Traditionally in art material choices can be quite standardized for sculpture, marble, bronze, etc. These are all excellent materials intrinsically; however, we find the magical thing about art is the ability to transform the undesirable into something beautiful. We see artists create this transformation with the depiction of a subject, taking an overlooked or everyday thing and handling it in such a way that it transcends the ordinary to achieve something almost sacred, think of the Jade Cabbage or Warhol soup cans, but this isn’t so common in the treatment of the materials. On a planet that decreases natural resources and increases waste, art can transform the perception of the value system around elements.

We have found that creating the challenge of working with something that is also sustainable is a great way to drive innovation and exploration. It has led us to go to sea to collect plastic, to the Amazon rainforest to obtain rubber from wild rubber trees and discover other sustainable rainforest materials, to human hair markets in Shandong Province, and to make a mobile furnace to melt aluminium cans into objects on the streets of São Paulo.