6 November–14 December, 2024

TAXON: A Solo Exhibition by Moses Hamborg

G/F, 41 Hengshan Road, Shanghai, China 200031

Shanghai, 70 Square Metres

Overview

SHANGHAI—70 Square Metres is delighted to announce the solo exhibition Taxon by our first residency artist Moses Hamborg, featuring his latest collection of oil paintings that delve into the concept of transcendence. The exhibition is also Hamborg’s first solo exhibition. Grounded in classical oil painting traditions, he employs a meticulous approach, drawing inspiration from real-life encounters to discuss shared connections that transcend time and culture and create works that resonate with the intricacies of various emotions and psychologies. Working with models over the past 2.5 months in Shanghai, Hamborg drew inspiration from Wu Xing; a Chinese philosophical concept rooted in the five elements, comparing physical differentiation in nature with the symbolic classifications imposed by humanity.[1]

Inspired by Renaissance painting, Hamborg’s practice is committed to the interplay of light and shadow through the use of classical oil painting traditions on jute. When the weave and rough texture of jute shows through the layers of paint, the pictorial plane conveys the underlying emotions and state of mind hidden beneath the surface of the subject.

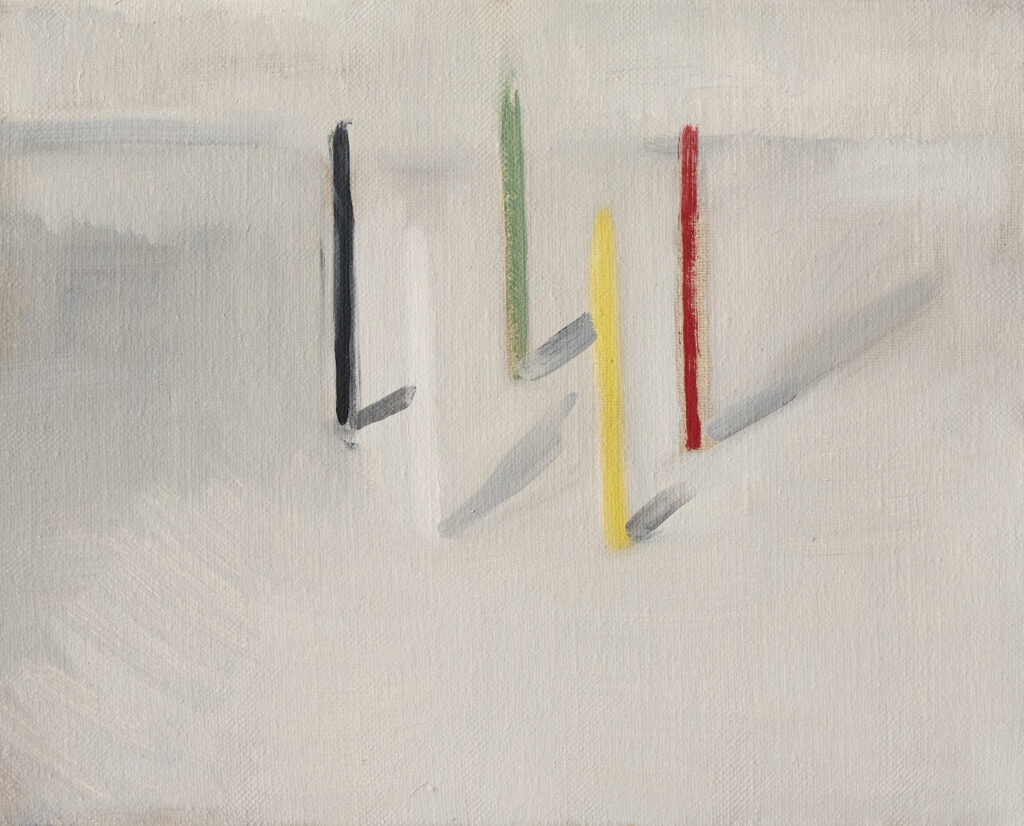

In Wu Xing, living species are classified into five groups: scaly, feathered, naked, hairy, and armoured, each aligned with one of the five elements.[2] Hamborg finds a parallel between this ancient taxonomy and Carl Jung’s theory of universal archetypes, where animals in dreams symbolise various aspects of the human psyche. For instance, dogs represent instinctual awareness , cats embody the feminine instinct, and horses symbolise the body and one’s physical health. According to both frameworks, categorical boundaries are transcended, with animals embodying symbolic weight beyond their physical traits. Hamborg is particularly fascinated by the intertwining state where distinctions fade and elements merge, making them difficult to differentiate.

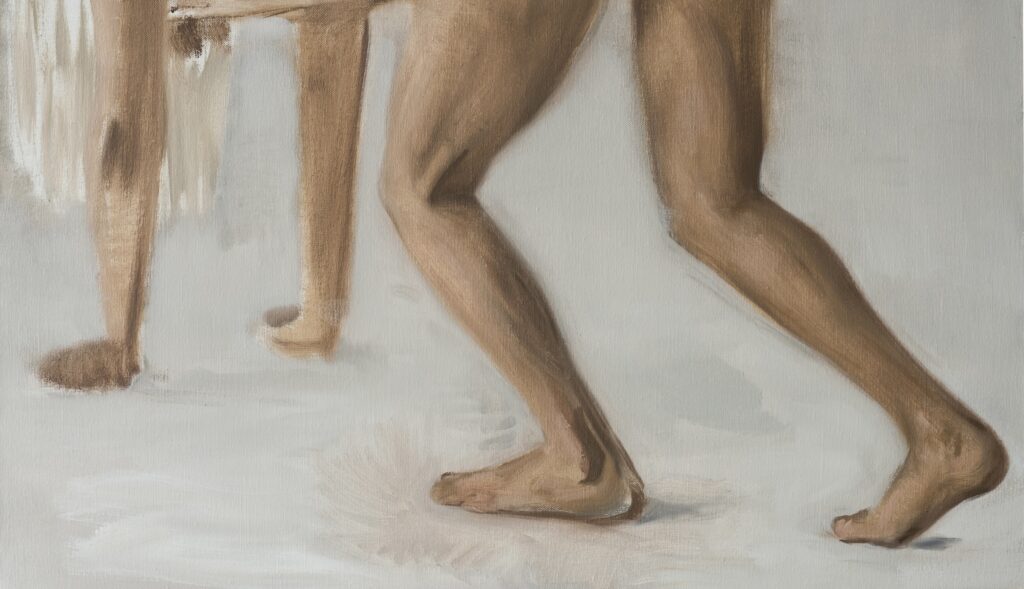

Throughout this presentation, Hamborg continuously poses the following questions: What are the fixed boundaries? Can the dynamic interplay between unconscious forces be rendered in a still image, or do they defy static representation? Hamborg is captivated by the in-between states where boundaries are no longer fixed. In Taxon, he employs a variety of ambiguity. The border between light and shadow is softened to emphasise the obscurity. Gestures are deliberately indefinite, blurring the lines between ecstasy and agony, rising and falling, waking and dream state. Figures hover in a liminal state, caught in moments of uncertainty that obscure the direction of movement, evoking tension between thought and emotion, control and surrender.

By manipulating light and applying a delicate visual language, Hamborg enhances the interplay between the physical and the symbolic, as well as the interaction between nature and the human psyche. His works exhibit exquisite details: bewildered and composed eyes, slightly furrowed brows, lean yet firm thighs, the fluffy essence of a cat and a dog, all contributing to their overall vitality and naturalism. Going beyond precision, Hamborg furthers his reflection on the personal and collective histories that shape our existence.

In Huishi, a young female figure is presented in a suspended moment when two horses are on the verge of stepping forward, piquing the viewer’s imagination and bringing forth a sense of unease. This painting is inspired by Henri Fuseli’s Nightmare (1781), reflecting Hamborg’s reinterpretation of the vanitas painting through the lens of Wu Xing. While the grapefruit on the ground symbolises abundance in traditional thought, the tension in the scene, along with the dead fish in the protagonist’s hand, serves as a reminder of mortality.

In Maurice, Hamborg examines the fluidity of gender. In the work, a figure with falling blonde hair is depicted with a slender body, yet their thighs display robust muscle lines, contrasting with conventional gender norms. The figure appears androgynous, embodying both the anima and animus, merging traditionally perceived masculine and feminine qualities into a singular identity.

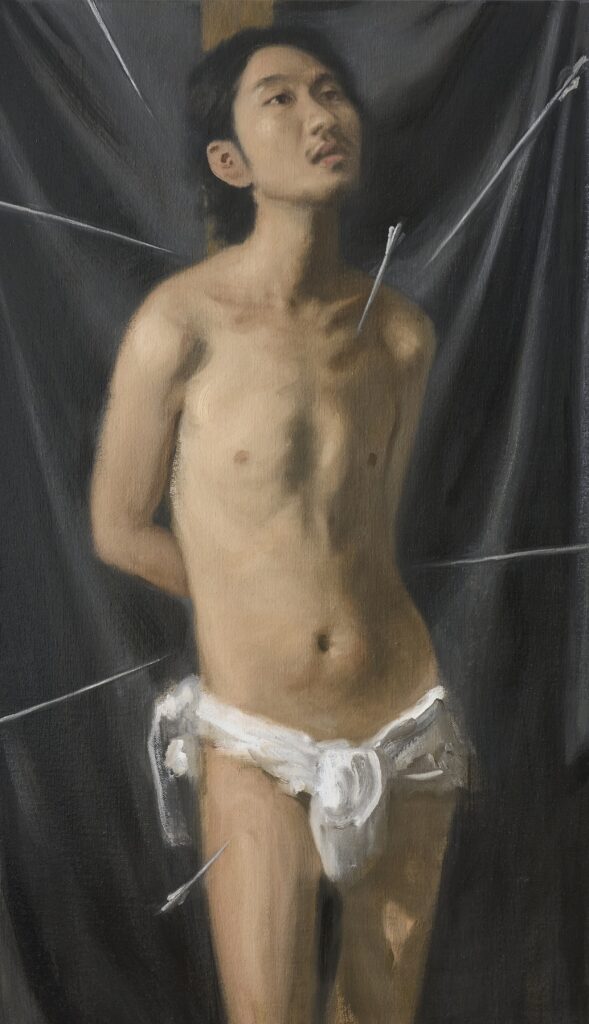

Sei takes inspiration from St. Sebastian’s martyrdom, presenting a semi-naked figure bound to a wooden beam with arrows protruding from the body and possibly more to come; once again, Hamborg’s main character is on the threshold. This scene not only reflects the crucifixion narrative but also references the Wu Xing, where the beam and the metal arrows represent wood and metal, respectively. At this pivotal moment, the figure’s calm and composed expression suggests the acceptance of fate and transcendence beyond physical pain.

In Hamborg’s works, unconscious forces interact within these still images, inviting the viewer to navigate the subtle, often unresolved emotions that flicker across faces like shifting light. Within this complexity, the artist highlights the fluidity of identity and the psychological currents that inform how we see and are seen, underscoring the ever-changing relationship between nature, identity, and the hidden layers of human experience. Ultimately, Taxon invites the viewer to reflect on the ways classifications can be established, expanded, and reimagined.

[1] Wu Xing refers to the five elements that form the existence and development of the universe in ancient Chinese cosmology: metal, water, wood, fire, and earth. The five elements not only correspond to natural elements but also connect with various other aspects such as seasons, musical notes, virtues, and colours, creating an interconnected system. For instance, “water” can simultaneously represent winter, the musical note of Yu, wisdom, and the colour black, becoming a member of the “water” family within the five elements.

[2] Li Ji: Yue Ling, c. 475–221 BC; Kao Gong Ji: Zi Ren, 5th century BC; Liu, Huai Nan Zi: Shi Ze Xun, c. 136 BC; Dong, Chun Qiu Fan Lu: Wu Xing Ni Shun, c. 136 BC