DC: Kazimir Malevich, the Suprematist artist, pursued a new realism painting using non-objective creation or in his words: “I transformed myself in the zero of form and emerged from nothing to creation.” To what extent is his idea or the avant-garde movement still relevant to painting now?

PP: Malevich’s most radical gesture with Suprematism was to present painting conceptually as pure rhythm. He says somewhere that Suprematism is like the symbols of ancient peoples – which were not merely ornaments, but things based on the expression of rhythms. That desire in Malevich to expose the rhythmic is perhaps what makes his work most relevant for painting. It’s about sharing a lived experience of time that is tightly bound up with negation – the negation of the object – as a means of expression.

DC: Going back for a moment to your comment about a Modern fixation on clarity – can you elaborate more on the notion of blindness in relation to abstraction and architecture?

PP: The more one analyses and sees dissected parts for themselves – the blinder one is to the borderlines where the parts meet. In Modernity, I think there arrives a much broader awareness of a ‘blind spot’. The new accelerated actual division of things – terrain, architecture, space in paintings – becomes doubled with a kind of shadow operation, where nothingness is also being divided in an obsessive way.

DC: What was the process of making the artworks for Country 10 at the Kunsthalle Basel? The artworks in this exhibition, in many ways, respond formally to Futurist artists. Furthermore, you re-edited a 1965 BBC documentary on demolishing a building of artist studios titled 28b Camden Street in London. What was the intention behind including a documentary in this exhibition?

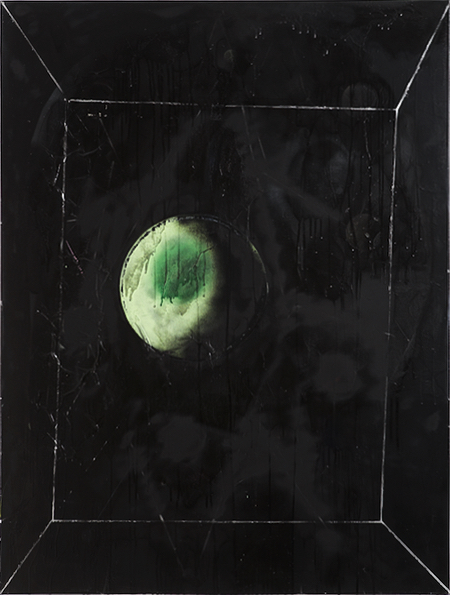

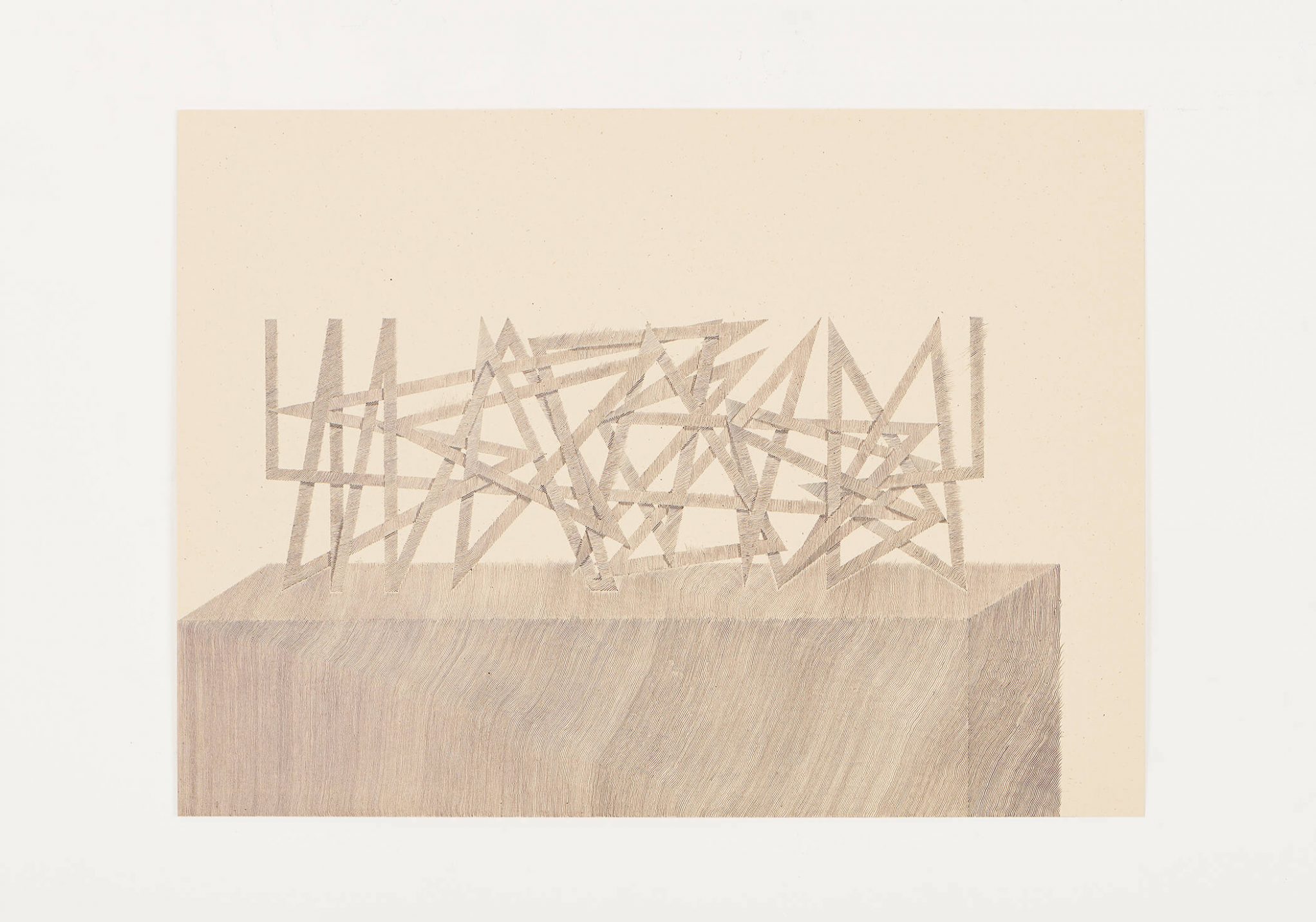

PP: The paintings in the exhibition were predominantly black, several had titles relating to housing and cities – they were all improvised. I worked on them very heavily until a linear structure that I liked appeared, and they got their energy from that way of organising composition – the friction between the painting and repeated effacing of forms. There was also a room of drawings on paper – very detailed and slow to make with the aid of a magnifying glass.

We found out that my grandfather Peter Laszlo Peri had exhibited at the Kunsthalle before the war, so he was already a presence in the exhibition. He narrates 28B Camden Street as one of the artists evicted from the studios. The overriding theme of the film is destruction and regeneration dissociated from time. I remember including my silent edit of the film in the exhibition because I wanted to juxtapose different temporalities – the film’s reproduction of dissolution against the manual processes of my work.

DC: Why did you title your 2014 solo exhibition at the Pearl Lam Galleries in Singapore The Reign of Quantity, and what were the intentions behind the series of paintings presented there?

PP: I was thinking a lot about painting in relation to different conceptions of time; cyclical, absolute, entropic, relative, virtual. Around 2012 I began to make paintings with masses of hand ruled lines. My idea was that the paintings would have a kind of separateness; they would gain autonomy if they got their point of perspective from accumulations of their internal marking out of space. The repetitive accumulation, the number of lines, made me think of the esoteric writer Rene Guenon and his idea of Modernity as The Reign of Quantity – a phase of materialistic degradation in the cycle of history.

I decided to use one of Guenon’s metaphysical formulas; cross = helix = sphere, as a geometric theme for the Singapore paintings. All nine compositions follow a horizontal movement of stacked lines interrupted by a vertical black strip – each painting’s colours vibrate differently as individual stations within that horizontal movement.