15 December, 2022 – 9 March, 2023

RECLUSIVE MEANS

Featuring works by Li Ming, Ni Zhiqi, Pang Tao, Qiu Deshu, Danful Yang and Zhu Peihong

Hong Kong

Overview

“Two recluses were ploughing a field when Confucius passed by with his disciples. A disciple went to ask for directions, introducing himself as a follower of Confucius. They said to him, ‘Rather than follow one who avoids certain people, why not follow someone who avoids society altogether.’”—The Analects of Confucius

Hong Kong—Reclusive Means is a cross-generational survey of Chinese artists who use different strategies to question social conformity. Their retreat from society is a conscious means of creating a critical distance for investigating issues of tradition, cultural symbolism, trauma, spirituality, consumerism and dislocation. The desire to provoke a necessary space for independent thinking is not only to satisfy a private longing, but more importantly is also to achieve a deeper level of understanding of the meaning of our existence in a rapidly changing world. As said by Yuan Hongdao (1568–1610): “Without an obsession, no one is exceptional.” Solitude is the very soil for artists to cultivate eccentricity in their pursuit of true happiness and contentment. In fact, eremitism has a profound history in China that dates back to the time of Confucius or earlier. For example, Zhu Da, otherwise known as Bada Sharen from the Ming dynasty, pretended to be a lunatic Buddhist monk and retreated to the mountain with the intention of escaping from society. In the current information age when intensive urbanisation has pushed many inhabitants to soul search in the countryside, true hermitry is no longer possible. Every aspect of our daily lives relies so heavily on the use of mobile technology for basic sustenance. The only feasible means is to augment our immediate surroundings into imaginary and alternative realities.

On view is a selection of artworks ranging from paintings to design objects and time-based media to convey a collective desire for seeking permanence in an increasingly contingent world. Not bound by the limitation of their immediate surroundings, these artists look to nature and their own personal histories as inspiration for their creative refuge. Reclusive Means sheds light on the issue of alienation as an impetus for art practice; the artists downplay explicit expressiveness with their works in favour of restraint, deliberately leaving audiences room to contemplate the subtleties of individual artworks. These post-modern literati vanguards extract the inner sanctum of our hearts and reconcile emotional distress with a sense of calm.

About Li Ming

Li Ming’s art practice is diverse. Primarily known as an artist working in video, Li often partakes in the narrative to explore the performative potential of video and the language of representation. With reference to the literati tradition, The Phantom That Is Screen is a video shot in black and white to express a deep sense of longing in a contemporary world. Dressed as a Taoist priest, Li unfolds a large kite in the shape of a mobile phone screen with a muted image and attempts to fly the kite in different urban and natural settings. Li states his intention: “When flying a kite, we need to gaze at it, interact with it in real-time, and create a relationship with it in our hands. It can be like a photograph—‘zoom in, zoom out’; it can be dragged, pulled and, crucially, it is also always in a beautiful landscape, photographed by a mobile phone. In this video, the kite and the screen are mutually exclusive; they are metaphors for each other and the fact that in our time, wherever we go, we will have a hand in the depths, pulling out the mobile phone, brightening the black screen and replicating the scene in front of us. In contrast, the screen becomes a black block planted in this scene. It is in this way that images circulate everywhere like ghosts.” By juxtaposing a blank still image from the phone screen on a kite in motion with the panoramic backdrop of an actual landscape, this unusual coupling of man-made and natural imageries speaks of our loss of a critical distance for observing nature and our immediate surroundings.

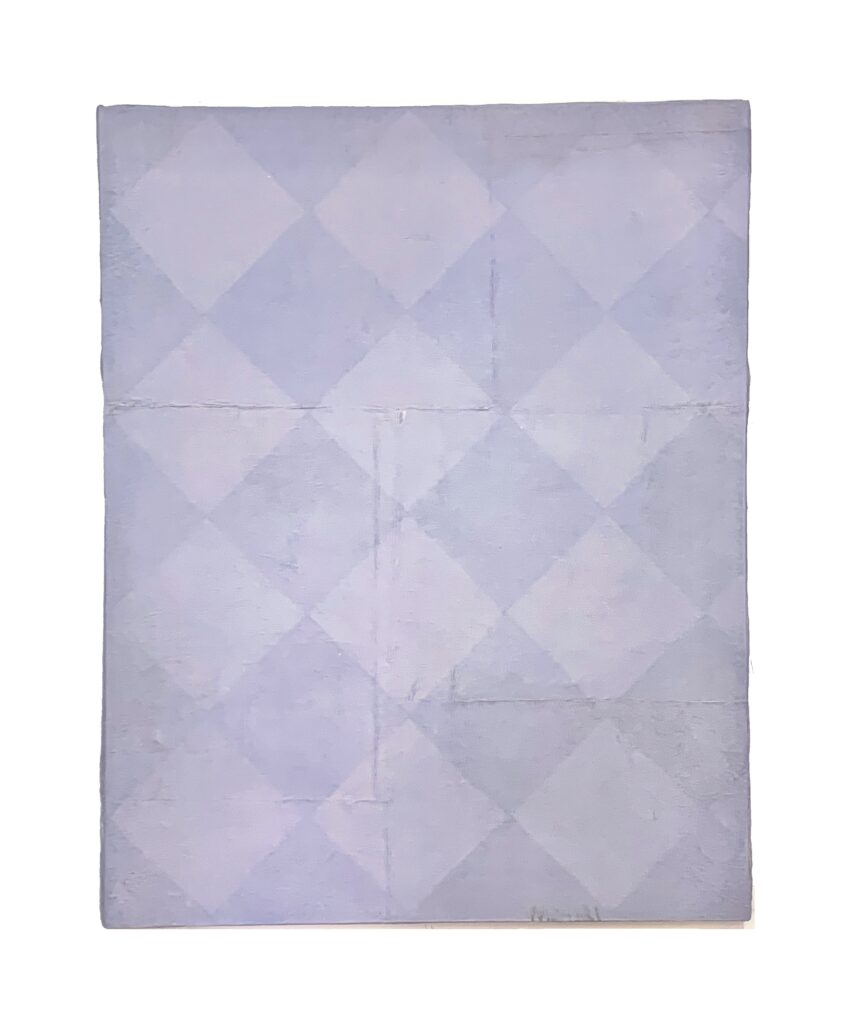

About Ni Zhiqi

In Ni Zhiqi’s Alhambra series (2017), which combines both collage and paint, the artist has chosen to cover the canvas with a specific handmade paper produced by ancient and secretive Chinese paper-making techniques. The works focus on the Alhambra’s tile patterns and evoke a feeling of infiniteness while recalling memories of the red palace built by the Moors in Spain in the Middle Ages. With the help of Chinese traditional techniques, his gentleness and warmth are slowly revealed. The core concept hidden in the faded colour and rough edges of Ni’s works is a philosophical outlook on time and memories from an Asian perspective.

About Pang Tao

Pang Tao is the daughter of Pang Xunqin and Qiu Ti, two important founding members of the early Chinese avant-garde art group the Storm Society (Jue Lan She), which was formed in the 1930s. Pang worked as an independent artist and an educator in academia from the 1950s to 1970s, a period marked by turmoil. Not interested in engaging with societal affairs, Pang was discounted as conservative, and her works did not spark much critical debate within the binary categorisation of art as either “new” or “traditional” at the time. Pang lived in Paris for a year in 1984 and was among the first group of artists who were sent to Europe to study art. Pang’s notable series Revelation of Bronze, which she began in the early 1980s, serves as a significant point of departure when she consciously moved away from realism towards full abstraction. In this seminal series, the artist flattens the imagery of bronzeware from the Shang dynasty in a meticulous manner and develops the painting through a formal exploration that goes well beyond decoration. The picture plane is imbued with colour patches of abundant variations of hues and fluid geometry to give the representation of a monolithic artefact an illusionary solidity.

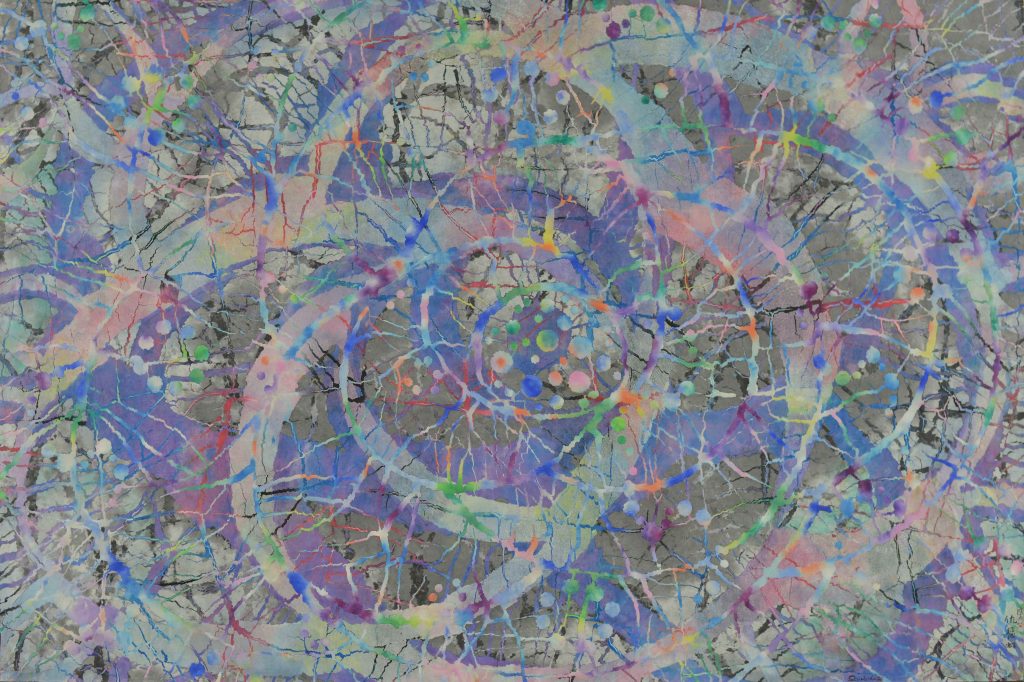

About Qiu Deshu

Born to a family of intellectuals in Shanghai in 1948, the late Qiu Deshu cofounded the Cao Cao She (Grass Society) with a group of artists who used the motif of wild grass as a manifesto for encouraging independent thinking. Marginalised by the art world at the time, Qiu suffered from unbearable psychological pressure, which caused him to experience a stroke and a brief loss of linguistic competence. As he was experiencing grief, he would walk around the deserted courtyard behind his studio. Deeply influenced by Chinese traditional philosophy, in particular Equality of Things by Zhuangzi, Qiu visualises natural transformation on both macroscopic and microscopic levels. An initial interest in the cracks in the rock slates subsequently led him to become aware of its silent but natural power. Qiu’s early experiment with Chinese ink painting encompasses tearing and rubbing Xuan paper and reconfiguring the paper fragments to form distorted images of landscape, or “fissures”, with lines that travel across the picture plane in a free-flowing manner. In essence, the Fissures series expresses his innermost desire for spiritual balance and self-healing, but it also proposes a dystopic vision of the rapidly changing landscapes of modern China.

About Danful Yang

Danful Yang, a Shanghai native, is one the earliest conceptual designers from Asia. Yang incorporates traditional Chinese art and craft techniques to create playful objects to reflect the consumerist culture of China. After the passing of Mao in 1976 and the Open Door policy in 1978, people began to rapidly change their lifestyle and gravitated towards Western attire. In a series of Untitled works, Yang attaches neckties and other sought-after elements of Western apparel to old Shanghai Art Deco chairs from the 1970s to comment on the changes in mindset during that period. For Packing Me Softly, Yang is interested in provoking other readings of packing boxes that are ubiquitous with online shopping. We always focus on the contents of a container and forget about the very function of the box itself. In a society where we are more concerned with appearances, we often overlook the need for basic materials and physical labour in order to service consumers. Yang’s own version of a taped packing box is made with hand-crafted silk embroidery, thereby infusing an everyday object with care and respect. This gesture functions as a parody to question the essential material needed for the circulation of commodities in a capitalist world. Drawn by the shapes of perfume bottles, Yang uses reverse painting, a technique that originated from traditional Chinese snuff bottles, to make her Inside Chic series. Miniature landscapes can be seen inside these stylised vessels that are housed individually inside a reflexive box to project a kaleidoscopic vision.

About Zhu Peihong

Interested in the different light qualities in a metropolis, Zhu Peihong’s My Space series focuses on the dots, lines and colour patches that flash in the picture in the process of creation as well as the traces left on the picture due to their convergence and dissolution. In this creative process, the strokes overlap and cover each other. The paint slowly drips and spreads, solidifies and stops, repeatedly until these fragmented traces, reaching an internal order, organically connect with each other and construct the conscious cyberspace perceived by the artist’s mind like a mental landscape of a utopia in between reality and virtuality.